Berries and Bodies: a Phenomenological Drama

ACT I : THE PERSONAL EXAMPLE

As I grow into myself in my thirties and finally feel comfortable in my skin, I’m unapologetically mashing my passions together and crossing my fingers someone else takes an interest. It’s fairly niche: art theory/aesthetics and grape-growing/ winemaking. I also make art, that is another part of me I haven’t managed to squash: exhibitionism, in the form of putting myself on display through art for public consumption. My main venue (currently) for this is my website Odd Wine-Country Thoughts where I write about grape growing and winemaking through the lens of art theory. My past interests and my current career have shaped me and won’t stay in their own pretty boxes.

Usually for O.W.T. I’m inspired by a quote from an obscure art theory book that I’m reading late at night to fuel my incessant art-interpretation of the world. Then I get up in the middle of the night, sometimes after sex is best, and bang out some sentences. I’ve lingered on the subtitle of arm chair philosopher, but really it’s just fiction, some structure, some references, some improvisation. I have been following the structure of two act ballets up until now, bi-party comparisons to illuminate grapes & wine through art, but there are more influences for this Loam Baby article so we’re up a few acts. I’m looking at grapes as a prime candidate for a phenomenological dissection, in particular the type of existential bodily-based phenomenology that Maurice Merleau-Ponty voiced in 1940s France. And then shedding light on this dissection as grotesque, and its application to aesthetics, offers a new framework through which to comprehend terroir.

Grapes and their skins are similar to us and our skin in that the environment around us is thick with influences that permeate into us and contribute in shaping our identity, or in the case of grapes, their terroir. This nebulous term terroir, and its Big 4 (soil, aspect, microclimate & human culture factor: farming), will make even the most versed connoisseur shiver a bit in their boots. The same goes for any philosopher who is asked to define identity. Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology rests on the idea of the skin as a porous membrane, that exchanges molecules with the environment that it is in contact with in a way that influences the identity of a person and that identity influences the environment in turn, or simultaneously. They inform each other and they inform the mind. Negating the mind/body dichotomy was to say the least, something close to this Frenchman’s heart. Phenomenology and Merleau-Ponty’s porous skin theory allows me to put berries and bodies side by side and compare their grotesque exchanges with the environment through the porous membrane of a skin.

ACT II : TERROIR AND IDENTITY

The corollary of envelope and interior on grapes and humans extends beyond the physiological into the murky zones of terroir and identity. The environment in which the grape tenderizes exerts itself upon the surface of the berry, penetrating into the skin to permanently alter the composition of the wine. As I began to write this the last berries were turning red on the Cabernet Sauvignon block where I buy fruit. From 50% veraison to fruit maturity is about 40 to 50 days. During veraison grape skins not only change color, they thicken and relinquish their hold on the pulp. I seem to be undergoing a similar transformation these days, my skin letting me down physically but accumulating “character” (I need not list the details of this process for you, I’m sure). Some instances of the air environment penetrating into the berry pericarp and shaping the molecular structure of the resulting wine are as devastating as smoke taint, and some are as remarkable and marketable as eucalyptus in Australian Syrah/Shiraz.

The same molecular mechanism is at play with grapes as with human skin: passive diffusion across the seemingly impenetrable membrane that holds the rest of our insides inside of us. Pheromones are the easiest example to start with, they are exchanged through intercellular passive diffusion through our epidermis, but our whole body is sensitive to many other stimuli through our skin. Stimuli that are usually associated with one sense and the corresponding orifice. Merleau-Ponty expanded “vision” to mean the body seeing & sensing a cacophony of stimuli working together through the cutaneous membrane as the main receptor, and not just the usual duos: visual/eyes, olfactory/nose, oral/mouth, auditory/ears. Skin senses light waves that make the color spectrum, feels air waves that make sound, and absorbs molecules that make up odors and tastes. That palpable environment all around us is what Merleau-Ponty called Flesh, he’s giving materiality to what looks at first glance like the void around us, even down to the detail of the molecules floating around in that void, that permeate into our skin and shape our identity. It’s interesting to note that Merleau-Ponty was published in France shortly after insect pheromone research first appeared in the published scientific world in the 1930’s, and then his essay on the Flesh “The Visible and the Invisible” was published in English in the 60’s simultaneous to the field of exocrinology really taking off.

Terroir, in light of the Flesh, can be analyzed by just the look of the environment as it is what creates the rhythm of sun exposure, fog and air circulation and a myriad of other climatic elements that fill up the space within which vineyards exist. This Flesh is all around the vine touching its every surface and interacting with it. It includes as well the soil that surrounds the roots where the history of the preceding months of rain (or not) and microbe populations from many years precedent play out on the vine throughout the growing season. The soil is also the realm of rootstocks and grafted to that the varietal which is the blood and genetics of the vine. All those variable constituents of terroir can be lumped into the idea of Flesh that Merleau-Ponty talks about, and matched accordingly to similar constituents that give us an identity: the environment that we grow up in and the fabric literally of that: the touch of clothes and a mother, the resonance of walls be it wood or plaster, the heat of a car from leather or fabric seats, or sweaty bodies next to you on a bus, and microbes for that matter, music, AC, wind speeds, smells from the oven, and on and on. These stimuli effect us in the present tense but also as a symphony of our past, stored up in memory. And of course our genetics are the easiest to compare in this analysis with that of vines. Like them, we also inherit better or worse resistances to microbes and drought, climate-related in the case of vines and emotional in the case of humans.

ACT III : REPRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION

In addition to skin absorption of phenols peaking during veraison, berries also become attractive to the mammal palate. A berry is a flavorful package that contains, protects and ensures from its deliciousness the dissemination of the seed within which sleeps the plant embryo. Their juicy sweet flavor is attractive to birds, wild turkey, deer and raccoons who eat the berries, walk around, and poop them out somewhere. Yeah in that nice patch of fertilization a new vine will pop up. The biological function of the grape is that of an ovary. But if they don’t get eaten, as is the majority of cases in Sonoma County, then they are harvested before they get a chance to complete the reproductive cycle. So they give birth to wine instead. Thank God. Back to the human body: our ovaries make babies too, but we also have the luxury of giving birth to art without having to sacrifice an unborn child. Art and wine are often compared for their equally complex sensory allure and the parallel processes of their enigmatic making.

I’m going to draw a new line of comparison for these two old chums wine and art to highlight their similar origins in reproduction. The making of wine from the ovary of the vine is a usurping of the reproductive cycle of the vine and differs little from the making of art, as that too is integrated to the reproductive cycle of humans. When humans make art they are also making themselves attractive to potential mates and acquiring skills to hold the interest of said mate. Art has evolved to be an essential attribute of the human species to effectively perform its function of propagating. This idea is clarified by Denis Dutton in “The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure and Human Evolution”, where he expands evolutionary science to include the human trait of art making within natural selection. He poses art as a principle fitness indicator when assessing for mating. What makes humans attractive to others, in addition to having good teeth and fast reflexes, are their capacities to entertain and be cultured: music, dance, song, art, theatre, jokes, etc., are all weapons we yield to stand out and attract a mate. Art making is therefore in integral part of the reproductive system of humans. And wine is an integral part of the reproductive system of grape vines, after some human meddling of course.

Grapes: the full pregnant bellies of the grapevine give birth to the wine and through them the terroir is conveyed. Humans, in addition to producing babies, produce art as well, this object that we make that is full of our identity and can be consumed, conveying our identity, thoughts and emotions to viewers. Phenomenology is also helpful to describe receiving end of art and wine, as the consumer or art viewer. This is where I first came across it, as a method for expanded art analysis while I was getting a Master of Fine Arts. Conceiving of the body as seeing, Merleau-Ponty helps assess art more holistically as having an effect on the viewer’s body by more methods and channels than just the eyes. This is one of the reasons art theorists love him, he offered an expanded way of assessing art at just the right time when artists were eschewing purely visual works and using new materials to create a multi-sensory effect. Carl Andre’s copper minimalist squares from 1969 are meant to be walked on and appreciated for their feeling different than a concrete floor and the subtle sounds they make as they heat up, expand and become un-level, clinking underfoot. Also in the 1960s Joseph Beuys’s absorbent felt sculptures effected the sound of a room, to the extent of being a palpable silence on the skin, an utter stillness, due to a lack of sound waves. These art objects influence the environment (what Merleau-Ponty would calls Flesh) that surrounds them and provokes a curated set of stimuli on the art viewer. Wine appreciation is also a multi-sensory experience and reflects the curated elements that go into terroir, such as vineyard establishment decisions, rootstock and clonal selections, irrigation protocols and farming practices. We taste the terroir in sensing the Flesh of the wine: color, taste, nose, and mouth-feel through our hands, eyes and the skin on the inside of the mouth. The confluence of orifices in the back of the mouth are fantastic: nose, throat and even ear canals are interrelated and work together when tasting.

The grape expunges into the bottle which is the vehicle for transmitting the terroir as I pour myself into my art which is the vehicle for transmitting my identity/mind-frame. Both the terroir and identity are etched into the bodies of the grape and artist in the scope of phenomenology, a theory on the nature of being that also helps dissect how terroir and identity are received on the consumer end.

ACT IV : THE GROTESQUE

If you look at a berry, pick it up and feel it, it is a nice smooth surface with all the goop tucked inside. Same when you look at a human, they are usually all buttoned up in some nice skin. Merleau-Ponty allows us to see the berry as a membrane immersed in a Fleshy environment that penetrates into it. The Flesh impresses itself upon the vine also through the leaves and the roots and the cultural practices of the people around that vine. It’s nitty-gritty, juicy and sticky, and beautifully grotesque. Now that harvest is upon us, I pulled samples the other day in the field, tasting as I went along. My hands were sticky, it got in my hair and the pendant clusters dirtied up my back as I passed under the canopy from row to row. It is such a beautiful respite from all the work I do on my computer on a screen trying to promote & sell wine.

The grotesque was up there, in the second act of this drama, in the two subjects that we’re examining, the berry and body skin membranes thanks to phenomenology. In the third act I lumped in some grotesque interpretations of the vine’s lifecycle and the reception of wine in the consumer to underscore breaking the illusion of a “clean, neat, contained and beautiful” grape berry in its magnificent and picturesque terroir. It is hard to break that illusion as consumers are so removed from the grapegrowing and winemaking processes. In fact, we’re quite sheltered from many of the goopy parts of life, I mean I didn't see a baby being born until I looked down and it was coming out from between my legs.

The grotesque body is a concept laid out in art theory as a counter part to beauty, contained and pure. Mikhail Bakhtin was the first to elaborate a structured framework of the grotesque through his examination of Rabelais’s bawdy fantasy satires. He explored the efficacy of grotesque tropes as tactics to undermine hierarchy and defy containment. (Bakhtin wrote his thesis in 1940 but it was not published in Russian until 1965, and then English in 1968, similar publication timelines to Merleau-Ponty and pheromone research). The grotesque is usually a visual thing with synonyms like repulsive and gross. In a more refined sense though it speaks about porous surfaces and the true nature of things as inter-relating, cross disciplinary and merging with each other, making babies and having them come out in goops of uterine lining and blood. It’s everything that is the real part of life that can’t be encapsulated in a marble statue or closed off containers separate from each other and separate from the world.

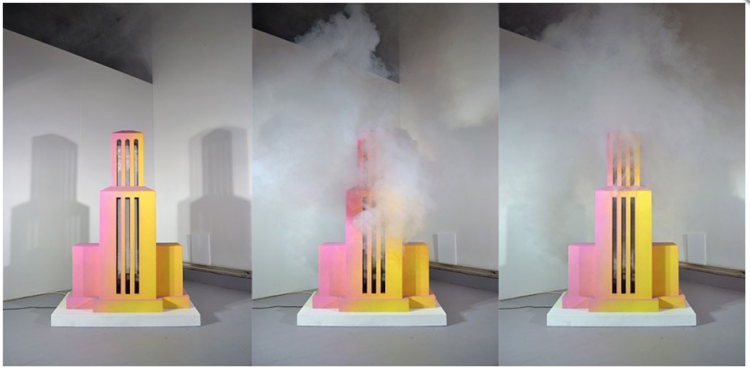

Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology happens to be a theory wielded in the realm of aesthetics to gentrify the field of grotesque as beauty’s lesser known but viable counterpart and equally successful path to the sublime (in some people’s opinion). The grotesque is big into porous surfaces and cross-disciplinary and oozing out and oozing in. So when Merleau-Ponty intellectualized what is essentially a grotesque perception of the body, it was a reminder that we are bodies and that we know the world through them, not apart, a mind anesthetized from a body. An art theorist might site an example such as Paul McCarthy’s Chocolate Factory as an embodiment of the grotesque, and although my subjects are a far cry from that, I find molecules floating in and out of my skin and the skin of berries to be a fitting application of the grotesque body theory. Especially since it helps to disrupt the classic framework within which we conceptualize terroir, the effect of which seems to render terroir an unapproachable term. To frame terroir within the grotesque puts into play the powerful tactic to disrupt and upend hierarchies, that usually makes things more approachable.

ACT V : A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR TERROIR

The illusion of being unaffected by the world around us is what the grotesque attempts to defy, and how we’ll mainly apply it to elucidating terroir. Seeing grapes just through the eyes creates the illusion of them sequestered from the world. Phenomenology pierces that veil and leaves room for the grotesque to enter the scene. Terroir and identity are both terms that people shy away from so I’m linking berries and bodies through phenomenology to illuminate that it is natural and to be expected that these terms are complicated and will never and should never be attempted to be reduced and put in clean impenetrable boxes, with neat compartments. They are both part of grotesque systems of propagation and survival, and one small aspect (compounds passing into skin) never stands alone but is also not to be neglected, as its interdependency with all the other aspects gives it equal power in influencing the whole system. It also never ends, another grotesque attribute, it cannot be completely considered nor encapsulated because terroir like identity are conveyed into products the wine and art that are meant to be subjectively consumed through oral/visual/olfactory/audio and cutaneous means.

We are so removed from the grotesque reality of the life of wine, when visitors drive by and look at a field of grapes and try and wrap their heads around the notion of terroir of course it's hard to understand. Beautiful wine country has so been drummed into our heads that it is hard to penetrate. You have to look closely at the way that terroir gets into those grapes and the grotesque nature of a vine as a giant reproductive organ trying to spread its tentacles all over the place; and producing delicious tasting fruit to get shit out by animals so it can spread its species; and on top of that consider the work of a grape-grower to contain and cut back and fine tune the vine to get the right flavors; and finally the winemaker who intervenes in the reproductive cycle to harness that flavorful ovary.

Image use courtesy of the artist Jessica Martin - “Muir’s Study” Acrylic on Arches paper, 2014. www.jessicamartinart.com